Vehicle Grid Integration (VGI)

Introduction

Vehicle and grid integration (VGI) is the the latest data centred challenge for Rangl, the new exciting AI challenge platform dedicated to control problems.

Electric vehicles (EVs) are by now part of our daily lives, with the likes of Tesla and Nissan helping to promote green and sustainable transportation. EVs are powered by efficient lithium-ion batteries that can be charged by the electricity coming from the grid, which in many countries is cheaper and has less carbon footprint than conventional fuels. Everything sounds great right?

However, as EVs become mainstream, our local distribution systems (DSs) will be faced with the ambitious challenge of supplying these powerful storages. This is some tricky business. As fast charging seems almost an unavoidable reality, DSs will be increasingly loaded with the power required for transportation and distribution system operators (DSOs) will have to choose between upgrading the current grid infrastructure or hindering the EV revolution. But what if there was another way?

Rangl presents VGI, which aims at providing solutions for optimising the operation of DSs while supplying and promoting e-mobility. This is a challenge for the current generation of data scientists, engineers, applied mathematicians to help promoting green transportation and safeguard local networks.

The issue of uncontrolled charging

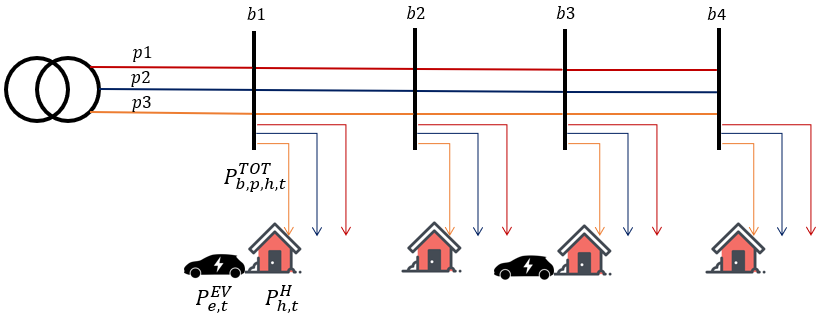

Let us consider a generic DS as shown below.

Where each household is connected to a certain phased of a connection bus , and will have a certain electricity demand, given by the household appliances for each time step . The householder may ov and EV, identified with the index , which will be connected to the household's low voltage network. A three-phase transformer will supply this DS. In this challenge , , and .

Each household will consume electricity each day, and EVs need to be charged for their journeys. In fact, EVs can depart for trips and come back afterwards. Therefore, the electricity used to charge the EVs, will be provided by the DS along with the electricity consumed by the household appliances, i.e. is the total electricity demand of the house and the EV. In this challenge, each day is represented by half hourly time steps.

In power systems, especially in DSs, electricity consumption leads to voltage drop. Hence, the higher the electricity consumption, the lower the voltage. There are statutory voltage limits that have been set to ensure a reliable operation of DSs; in the UK these limits are -6% from the nominal voltage of 230 V, to +10% of the nominal voltage. Therefore, for a safe, reliable and efficient utilisation of DSs, the voltage must always be kept within these limits.

As EVs are additional loads to the DS, charging them will inevitably cause voltage drop. The key is to minimise the voltage drop in order to comply with the statutory limits. This is what VGI is all about: smart charging that satisfy EV drivers and protects the DS.

Working principles

There are two key objectives that need to be fulfilled in this challenge:

- minimising the voltage drop in a DS;

- sufficiently charging all EVs prior to their departure.

The architecture of the challenge includes two essential parties, namely the environment and the agent, which are typical elements of reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms. RL is a key part of Rangl, where an agent interacts with an environment to improve its performance. The environment provides feedback to every action of the agent in the form of rewards, and observations of the current state of the system.

To this end, the environment fulfils the following duties:

- implement any action performed by an agent and calcuate an associated scalar reward;

- provide an observation of the current state of the system.

The agent must attain the following tasks:

- intake the reward and observations provided by the environment;

- formulate an action based on historical observations and rewards.

Environment - a typical distribution system

In VGI, the environment is represented by a DS with 96 houses, distributed accross the three phases of a four-buses low voltage network. An arbitrary (known) number of houses include an EV. The environment updates its state every time step of half an hour; hence, there are 48 time steps in the simulation of one full day. The key parameter in identifying the state of the environment is the voltage. Other parameters are the prediction of the electricity power consumed by each household, arrival (at home) and departure (from home) times of EVs and the energy stored in the EVs. All the observable elements are provided in .csv files for each simulated time step. The observation package at each time step consists of the following elements:

- Arrival times of EVs, ;

- Departure times of EVs, ;

- Required energy for next trip, ;

- Energy stored in the EV, ;

- Voltage of the DS at the current time step, ;

- Prediction of household electricity demand , where is the forward looking time period.

Each reading is an array of 96 elements, as same as the number of houses, ; the houses that are not equipped with EVs will display suitable information that will help to discern this unavailability. One exception is the prediction of the household electricity demands, provided for the next 48 time steps. Naturally, this predicted infromation has uncertainties.

Arrival and departure (at and from home, respectively) times are randomly generated from normal distributions:

- Arrival times have a mean and standard deviation .

- Departure times have a mean and standard deviation .

At the beginning of each simulation day, the initial energies stored in the EVs are generated randomly. In VGI, the maximum energy capacity of any EV is 30 kWh.

Once the total electricity demand of each household has been determined, a power flow simulation is run to determine the system voltage. In VGI, OpenDSS is used to calculate power flows: OpenDSS is an open-source software for DS analysis, that allow power flow calculation, transient analysis and fault analysis (more information is available here).

Agent

The agent must use the available information, i.e. observations and reward to formulate an action policy. In VGI, the action policy is a set of variables, representing the charging strategy for the EVs in each household, i.e. . If a household, with index, is not equipped with an EV than any variable at index of the array will not be considered towards the formulation of the total demand.

Step

At each simulated time step, the following steps are undertaken by the environment:

- Read action policy, , submitted by the agent.

- Calculate total power demand of each household as .

- Calculate total electricity demand at each phase of bus at current time step as .

- Run OpenDSS to calculate voltage .

- Check if EVs are sufficiently charged; , if ? Calculate mismatch penalty.

- Update prediction of all household electrcity demands .

Reward

The reward is calculated based on the two key objectives of VGI, namely system voltages and energy condition of the EVs prior to departure. The following expression is employed:

Where, is the reward related to the voltage deviation in the DS, formulated as follows:

Where is the nominal voltage of 1 per unit. The above expression enforces the statutory voltage limits: if the voltage exceeds the limits then the associated reward is zero. On the other hand, if the voltage is within the said limits, then the reward is porportional to the associated deviation from . It can be seen that the voltage reward can assume utmost unitary value.

is the reward associated to the satisfaction of the charging requirement fro travelling, as expressed hereby:

where is the set of indeces identifying the EVs that have not yet departed at the current time step. The reward formulated above provides a penalty if the energy stored in a departing EV is lower than the energy required for the trip. As also the energy related reward can assume utmost unitary value, the total reward can be utmost unitary.

Getting started

Prerequisites:

- Docker (get it here)

Download the code:

git clone https://gitlab.com/rangl/challenges/vgi.git

Create a Docker image:

make build

make shell

Install the required packages:

pip install -r requirements.txt

Run tests to ensure the correct operation and parameters

make shell

cd vgi/envs

make clean && make test

Install the custom gym environment

make shell

pip install -e

./example.py

Training and evaluation of models

Technicalities

Currently, the most recent branch is linearised_voltage, to which I am refering in these notes. Specifically, we are using the code in two files: src/example.py and src/plots.py.

The code that can be used for getting started with training is located in the file src/example.py, which needs to be executed from within docker as explained above. Because of some permission issues on the linux/docker line I couldn't put various RL and heuristic agents into septate files so depending on what you want to do you must uncomment an appropriate section in src/example.py.

Currently, it has some introductory code (section 0.) and clearly marked 4 sections: 1. training, 2. evaluation, 3. do-nothing agent, 4. full-charging agent. If you want to play with it, execute one secton at a time.

Training

We are using RL algorithms implemented in the library stable_baselines such as ACKTR. We also used TRPO in the previous challenge (OPF).

While debugging I set N_STEPS = 12 to speed up learning, taking into account that we are mostly interested in what happens before the vehicles departs. Later on we may consider one whole day by setting N_STEPS = 48. Also, currently the network consists of 1 house only.

We crete an environment, reset it and record its initial state as observation by executing

env = gym.make("vgi-v0")

observation = env.reset()

We specify the number of epochs (days) that we want to use for training e.g. STEPS_MULT.

It is beneficial to check how the model is performing every now and then, so after the learning is completed we simulate N_test days, save the rewards in a data frame and pickle the data frame. The whole process is repeated, for instance N_train times.

If we take

STEPS_MULT = 100

N_test = 10

N_train = 40

the procedure takes about 1h to complete. In summary, with these values, we train the model on 4000 days, evaluating the model every 100 days using a sample of 10 days.

We select a model from stable_baselines e.g.

model = ACKTR(MlpPolicy, env, verbose=1)

The training is performed using the following code. Note that the trained models are saved periodically.

rewards_df = pd.DataFrame(columns = ['iteration_'+ str(x) for x in range(N_test)])

for i in range(N_train):

# training

model.learn(total_timesteps=TOTAL_TIMESTEPS)

model.save('TRPO_'+str(i)) # can't choose a different directory because of the issues with docker

# evaluation

rewards_list = []

for j in range(N_test):

rewards_list.append(run())

rewards_df.loc[i] = rewards_list

print(np.mean(rewards_list))

rewards_df.to_pickle('rewards_df')

Plots of the learning curve

We can now plot the learning curve, which gives average reward versus number of iterations and enables us to see whether the agent was improving during the learning process or not. This can be plotted using the code in src/plots.py (which I normally execute outside the docker container in my Python editor's console).

rewards_df = pd.read_pickle(current_directory + '/vgi/src/rewards_df')

plt.plot(rewards_df.mean(axis=1))

plt.xlabel('number of iterations x100')

plt.ylabel('mean reward')

Agent sanity check

The next step is to see what actions is the trained agent performing and what effects on the environment they have. In the file src/example.py, use the following to read one of the models saved during training

model = ACKTR.load('TRPO_39.zip')

The function observations_data_frame_model() simulates one day and outputs 3 data frames: observations, actions, rewards. Additionally the two components of the reward can be directly read from the environment:

rewards['voltage_rewards'] = env.voltage_rewards

rewards['EV_rewards'] = env.EV_rewards

The three data frames (observations, actions, rewards) are then saved.

Once more, outside the container (code in the file src/plots.py) the data frames are loaded and the plot() can be executed producing 6 graphs, which show the most important elements of the environment:

- state of the EV's battery ,

- requirement and predicted departure time ,

- total reward and the EV part of the reward ,

- voltage ,

- hausehold demand in the next step ,

- actions taken by the agent.

observations = pd.read_pickle(current_directory + '/vgi/src/observations_random_agent')

actions = pd.read_pickle(current_directory + '/vgi/src/actions_random_agent')

rewards = pd.read_pickle(current_directory + '/vgi/src/rewards_random_agent')

plot(observations,actions,rewards,0,True)

Comparing with the do-nothing agent

It is instructive (especially while debugging the environment) to compare the reward and overall behaviour of the environment with an agent which does nothing all the time i.e. submits action equal to 0 at all times.

This can me done in a similar manner as evaluating the trained RL agent.

In the file src/example.py the function observations_data_frame_zero() needs to be executed and the observations, actions, rewards data frames need to be saved. Then as before, the plot() function in src/plot.py produces 6 graphs of various components of the environment and calculates the cumulative reward (to be compared with the RL agent).

Comparing with the max-charging agent

Another simple agent, which can be treated as a benchmark is the one which submits maximal action (equal to 3) at all times, regardless of whether the EV requires charging or not.

Similarly as before, in the file src/example.py the function observations_data_frame_full() needs to be executed and the observations, actions, rewards data frames need to be saved. Then the plot() function in src/plot.py should be executed and the results compared with the RL and do-nothing agents).